RESOURCES for Avalanche Educators

By: Zack McGill

First off, whether you are a new instructor about to instruct your first avalanche course or a seasoned course leader, thank you for being here. The purpose behind The Avalanche Educator Resource is to provide a place to compile resources, activities and lessons specific to recreational Avalanche Courses offered in the United States (Level 1, Level 2, and Avalanche Rescue).

This resource is by no means a replacement of the curriculum and tools provided by AIARE, AAI, or other AAA blessed providers of curriculum, but a supplementary resource that can take your teaching game to a higher level. Feel free to take any of these activities and use them as they are, adapt them to fit your style, and share them with other instructors. This resource is hardly inclusive of all that’s out there, but we would love for it to be. So if you have an activity or lesson that you think is worth sharing, please contact Zack McGill: zack@cascademountainascents.com and he’ll get it up here.

If you see some activities that you already use listed here and you’re sure you were the true master mind behind the activity, just let me know! Happy to give credit where it’s due. Many of the activities listed are from folks who don’t know where exactly they came from, but thought they were worth sharing. It’s all in the spirit of making the community better.

Zack’s Soap Box

This section is my opportunity to use this forum to have a soap box moment and convey my thoughts on the avalanche education industry and this resource. I hope that you read it… If you’re just here for the activities and could care less my views, that’s cool too. You can SKIP AHEAD to the activities.

We have an important job as avalanche educators to set students up for success. Our mission is to save lives. This shouldn’t be taken lightly. The people we send out into the backcountry after our courses make decisions based on what we’ve taught them. We owe it to them to deliver a quality product!

This is easier said than done, however… especially if you’re a new instructor. Tweaking your powerpoint presentations to include your own photos, knowing what slides or text to take out, inserting engaging activities into lessons… this all takes time, but it’s those personal touches that make the material relevant and memorable to students. In my experience, most providers don’t pay instructors or course leaders for the time they spend updating their lessons before each season, or, if they do, it’s not very much.

Some instructors are intrinsically motivated and put in the time to make lessons exceptional regardless of whether they’re getting paid or not for that labor. I’ve also sat through quite a few “death by powerpoint” presentations and heard dozens of horror stories from students and fellow instructors who’ve suffered the same. As one of those intrinsically motivated humans, those presentations hurt me, but I understand why some folks would just put in the minimum effort required to do the work. Why should they do work for no compensation? Really… they shouldn’t.

If you are a provider of avalanche courses, you should provide some amount of compensation for pre season prep. That can take the form of paid training in the field and the classroom or just paying hourly for the work they do. I think most humans who get into this work are well intentioned, just not set up for success. Compensating folks goes a long way to encourage them to put in the work to make an exceptional product.

I personally spend DAYS reworking my presentations and activities before each season to include the latest and greatest tid-bits from humans way more intelligent than me. Good news is… avalanche courses pay way better than day guiding, so I feel that extra effort is somewhat compensated for in the long run. Kind of…

Avalanche courses should pay better because they require a more robust skillset. You not only need to understand the data and nuance of avalanches, but also be able to package that information in digestible and well-scaffolded pieces so students actually retain some amount of the fire hose of information we blast at them. This of course is in addition to the ability to guide other humans in hostile environments, ski or ride well, and have at least a WFR/CPR cert.

Some folks are naturally good educators, but even the most gifted educator needs mentorship and guidance to do this job well. So if you’re just starting out on this journey to teach avalanche courses, don’t worry… even if you aren’t naturally gifted at teaching, you can still learn activities, tips, and tricks to provide amazing lessons to students. This resource is a part of that, but hopefully you work for a provider that recognizes the importance of mentorship and training and creates opportunities for professional development.

If you’re a veteran instructor or course lead, do your part to be mentors and leaders in the industry. Provide feedback to those newer to the game and go out of your way to be there. We all stand on the shoulders of those that came before us. I wouldn’t be where I am without the extra effort of folks like Joey Thompson, Mike Soucy, and many others who put on trainings or let me buy them a beer or dinner in exchange for letting me barrage them with questions.

Hopefully if you’re still reading this you’re in it for more than just the paycheck and seeking to learn something new, become a better educator, and further the mission. I hope this helps you on your journey.

-Zack McGill

Contents

This resource is broken down into eight sections:

- Organization (Resource for Course Leads and Providers on how to build an effective itinerary)

- Zoom Teaching Strategies (Resource on tips and tricks for those teaching primarily online)

- Level 1 Classroom (Activities and lesson plans for online and in-person classroom for the Level 1)

- Level 1 Field (Activities and lesson plans for the field for the level 1)

- Level 2 Classroom (Activities for online or in-person classroom for the Level 2)

- Level 2 Field (Activities and lesson plans for the field for the level 2)

- Avalanche Rescue (Activities and lesson plans in the field specific to the Avalanche Rescue Course)

- Continuing Education (How do I get better?)

Click around to what you need and again… please reach out if you have any other additions or have something you’d like to see!

The Power of Organization

Where my Course Leaders or Providers at? This section is for you. Whether a course is ultimately successful comes down to you and how organized you are. On a single course you’ve got 18 – 24 students, your instructor team, folks shadowing you, and potentially a grip of gear rentals needing to go out to folks who’ve never held a split board in their life. That’s a lot of kittens to wrangle! The most powerful tool to keep things on track (whether doing in-person or online classroom) is a well organized and thorough digital itinerary.

Itineraries will look different based on your venue and if you are teaching in-person or online, but here’s an example itinerary: Sample Itinerary for an AIARE 1 & AIARE 2 utilizing an online classroom.

At the least, all itineraries should include these pieces:

- Realistic lesson, activity, and break times.

- Who is teaching the particular section.

- The major points you’re teaching (to make sure that you get them all).

- Hyper-links to whatever resources, videos, websites, or activity descriptions you’ll need where you’ll need them.

Times

It’s important to set realistic time goals and then hold each other accountable to staying within those time margins. It’s easy to get into the weeds on topics (especially with students that ask a lot of questions) but remember the sage wisdom of KISS… Keep it simple, stupid. If you go over the time on one lesson, you’ll be rushing through the next.

Who’s Up?

Make sure that any teaching topics are assigned at least a week in advance so that instructors have time to prepare their lessons and even receive some feedback from you or others before going live. For new instructors you’re working with a lot, it’s nice to have them teach the same thing a few times to gain confidence and adjust their presentations/activities. They then can observe you teaching other topics a few times before eventually transitioning into teaching those themselves.

Major Points

It’s easy to lose track sometimes of the big picture goals of each lesson section, so write them down in a few places! Towards the beginning and ends of your presentations, in the itinerary, and/or in quizzes or polls! Repetition is actually needed for retention so hit the important bits hard.

Hyper-Links

You’ll notice in the sample itinerary that anytime a link needs to be put into the chat, that link is right there in the itinerary. This makes it easy for those presenting to move into the next activity or topic without having to click around to different pages or lose their place. You’ll also notice that the links go to activities and resources that live on our business operations google drive. This way, whoever comes in to work an avalanche course for us doesn’t need to know anything about how we organize or structure our online resources or how to access them. All they need is the itinerary and they link directly to those resources. Huge time saver.

Zoom Teaching Strategies

Provided by: Nicholas Vincent “Vince”

Below are some considerations for instructors to maximize their effectiveness in teaching over Zoom. The platform has several tools that apply to teaching avalanche education and in many ways can make us more effective educators. Remember… just because these tools are available doesn’t mean you have to use them all. I encourage everyone to figure out what works for them. It would be great to continue accumulating feedback and best practices within this document as we progress in the fourth discipline that is Zoom.

The video below is a great place to start. It highlights a good sample of best practices for teaching in a virtual classroom and the tools available in Zoom. Many of the items listed below came directly from its content. More functionality is available but these tools will get it done. This video was a collaboration between AIARE and AAA.

The password is: zoomtips2020*

Considerations for Course Leaders Pre-Course

- Assign co-hosts before the meeting starts. This allows the co-hosts to enter breakout rooms and let people into the meeting from the waiting room.

- Have a tech person to answer chat questions, post links, and troubleshoot technology

- Have your links that you plan on sharing preloaded in your browser tabs or in google drive.

- Message people in the waiting room that you will begin shortly.

- Ensure, the best you can, that technology is reliable and ready to go. Everyone should be on their PERSONAL laptop. Swapping laptops is not ideal. Highly recommend dual monitors for presenting.

- Provide some Zoom etiquette, training, norms right away.

- Collect Field Group Information right away!

On-Screen Strategies

- Lighting – Ensure your face is lit up so people can see your mug. Lights/sunshine behind you create an insufferable glare. Drop the blinds or turn those lights off.

- Background – The virtual backgrounds are cool. Just make sure nothing that shouldn’t be in a classroom isn’t behind you. I appreciate when people speaking have things behind them that give clues about who they are.

- Eye Contact – Look at the camera (or past it) when addressing the class. Try not to focus on the class or elsewhere for too long. Keep a good balance of eye contact.

- Speech – Just talk naturally as you would to anyone. Be aware of your volume and don’t be a robot, use inflection.

- Non-Verbal Comms – Use your hands and arms when teaching. Move back and forth into the camera. It’s easy to just sit back in your chair and talk. Engage the class by being dynamic.

- Headphones with Mic – This is the ideal setup for clear voice delivery and audio.

- Computer and Monitor – Do NOT use anything besides a computer to teach. Zoom functionality changes on phones and tablets. It also becomes increasingly unreliable and wonky. Two monitors are highly recommended if using PowerPoint. Swapping laptops is also not ideal but does work.

- Provide Direction – Give people clear and concise directions to how they should respond in a particular order, what they are doing in breakout rooms, and how

- Timing – We only have 7 hours between the two classes. Use your time wisely and stick to your itinerary.

Teaching Tools

- Chat Box – Use the general chat box to provide links, info appropriate for the whole class, ask/answer questions, and as a tool to solve issues. Coach people to private message instructors for tech problems or other personal issues/questions to avoid blowing up the general inbox.

- Screen Share – As you know, this is used to deliver media presentations or anything else on your screen. It is CRUCIAL that you check the 2 boxes at the bottom of the ‘Screen Select” prompt after initially clicking screen share. Both Share Computer Sound and See pic below.

- Students can also share screens which can be helpful in breakout rooms

- Two monitors are HIGHLY recommended

- Annotate is a feature within screen share that lets folks draw on your screen. This can be used to fill out trip plans, markup photos, draw in descents, etc. Its located on the drop-down bar at the top of the screen. If it’s not there, it might be in the options menu. Every student has access to draw at the same time and their drawings are labeled with names. Lots of fun options to explore here

- Breakout Rooms – This is a fun tool that lets folks work in small groups. You can pre-assigned groups before class or randomly during the meeting (pic below). See strategies and screenshots below

- Share screen and chat functions are localized to individual break-out rooms.

- Host and co-hosts can bounce between breakout rooms to facilitate or share resources

- Take screenshots of the work done in small groups to later share with the entire class

- Provide links to the whole class via the chatbox and have them click it BEFORE the breakout session.

- Use a Google Doc via instructor shared screen to record ideas/info in small groups.

- Under options, you can assign a timer which is a nice feature

- See additional breakout room options below in the screenshot

- Zoom Help Center Breakout Rooms Video

4. Reactions and Nonverbal Feedback – These are a good way to get a quick gauge of how people are doing. Reaction options depend on which version of Zoom people are using. At a minimum, it will have clapping hands and thumbs up.

5. Polls – These are a great tool for checking understanding, giving a pop quiz, eliciting feedback in the middle of a lesson, and lots more.

- They can be preset before the meeting or even during. Polls will provide

- Max 25 polls per meeting

- The host has a poll function on the toolbar

- Answers can be anonymous

- Answers can be a single answer or multiple choice

- Polls give results that you can share with the class

- Zoom Help Center Polls Video

6. Whiteboard – Just like it sounds, it’s a whiteboard everyone can annotate. Its located under the screen share feature and comes up as one of the options during the “select screen” prompt.

Back to Top | Back to Zoom Teaching Strategies

Level 1 Classroom

The following activities and lesson plans can mostly be used for in-person as well as online classroom sessions, though some are certainly specific to in-person. More and more, folks have embraced the online classroom, and though I enjoy teaching in person classes, I see why. It’s way easier for folks to not have to take a day off from work and just use their weekend to complete a course than to take a Friday off.

For online Classroom, Zoom is a fantastic tool for teaching if used effectively. One of the best features is the ability to do breakout rooms and split people into smaller groups to work through an activity. This forces students to actually interact, have opinions, and engage with the material in ways that a larger group setting just can’t. Instructors can then bounce around between breakout rooms to answer questions and provide guidance where needed (just like you’d do in-person).

Regardless if you’re doing in-person or online classroom, there’ll be some helpful activities and lesson plans in here for you!

Course Introduction | Avalanche Problems | Track the Season’s Conditions/Snowpack | Human Factor | Avalanche Terrain

Course Introduction Activities

Starting off courses with activities is a good move all around. It’s a great way to break the ice and get folks talking/engaging with each other and the material. Below you’ll find some activities to bring in at the start of your level 1 course.

Case sTUDY ACTIVITY

Provided by: Zack McGill

To get students immediately engaging with the AIARE Framework as well as each other, this activity is designed to be used in conjunction with a case study at the very start of course. In this example, we use the classic Hatcher Pass Case Study, but it can be adapted to whatever Case Study you want to use. I like having folks read through it individually first and then show the video.

After the video, then do the breakout room or in-person activity below:

Case Study: Hatcher Pass Case Study

- Introduce yourselves.

- Choose Speaker (Person responsible for presenting findings to large group and who will lead you through the breakout room).

- Link reasons why this accident happened to parts of the AIARE framework:

- Room 1: Prepare – How familiar were they with conditions? Were they familiar with avalanche rescue? What experience did they have in avalanche terrain? Was this good experience?

- Room 2: Plan – What were the group members like? How much experience did they have? What did they do to anticipate the hazard? Why do you think they ignored their pit results?

- Room 3: Plan – What was the route/terrain they chose to ride like (simple, complex, slope angles, etc.?) Did they have an emergency plan? What did they do once the emergency happened?

- Room 4: Ride Safely – What did they do to monitor conditions along their route? Did they check in with the group or reassess the plan? What was the terrain like that they rode? Did they use terrain options to reduce their risk? Or increase it? What travel strategies did they use that worked well? What travel strategies did they not use?

- Room 5: Teamwork – Do you think they used good teamwork? Do you believe every voice was heard? What was their group culture like?

- Room 6: Debrief – Pretend that it was your squad that was involved in this incident. How would you debrief the day/incident? What were conditions like? Did you make good decisions? How would you improve the plan so that nothing like this happens again?

4. Present to the rest of the group once the breakout room ends.

Confirmation Bias & Monkey Business Activity

Provided by: Daniel Simons with adaptations by: Kenzie Carson

LEARNING OUTCOMES:

● Students will be able to define confirmation bias and link it to how bias may inform decision making in the backcountry.

● Students will have an understanding of the importance of checklists as a tool to combat confirmation bias

VIDEOS: Monkey Business Illusion

PRACTICE/ACTIVITY:

This activity can be structured by watching the video first then breaking students into small groups to discuss ideas of how to combat confirmation bias

OR

This activity can be set up by defining confirmation bias first (Confirmation bias is the tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information in a way that confirms or supports one’s prior beliefs or values), watching the video then discussing in small groups ways to combat confirmation bias.

Prompts for student discussion:

■ What were you focused on in the video? (Likely the thing you were told to look out for, contributing to tunnel vision)

■ If you noticed the curtain changing, the player in black leaving or the gorilla, what allowed you to notice those things?

As students are brainstorming and discussing learnings from the video, point them to the Assemble Your Group checklist in the upper right hand corner of pg 2 of bluebook and terrain mindset on pg 3.

Describe the importance of checklists and routines in countering bias in individual and group decision making.

Checklist and Teamwork act as a backstop for our blind spots. The checklist catches the things we forget or aren’t paying attention to, other folks may notice things we are not noticing and be able to contribute to a broader understanding of terrain, weather, snowpack or human dynamics.

Demonstrate how the two tools on pg 2 & 3 of the blue book help guide a daily mindset to combat bias once you and your team are in the backcountry.

Zoom Intros Activity

Provided by: Zack McGill

If you’re using zoom to teach online classrooms, it’s good to introduce students to the tools and etiquette they’ll be using for course before blasting too quickly into the curriculum. To keep things timely, it’s nice to combine the teaching of zoom tools and etiquette with student introductions!

- Start off your introduction by launching a poll asking folks on their level of experience with zoom from novice to Jedi master (or whatever you want to put in there). This gets them acquainted with the polling feature and lets you know who those folks are that will need extra help and maybe those students who are better at zoom than you are and can help you out if you start to blow it!

- Show them where mute for audio and the video on/off buttons are and talk through expectations around those things. I default to videos always on unless we’re taking a break or you’re going to do something that none of the rest of us want to see. I also like to show them where the reactions buttons are since every once and a while I’ll be asking for a thumbs up if they’re done reading something and those little emoticon thumbs stick around.

- Show students how to change their backgrounds so that they can hide any distracting or unprofessional/embarrassing surrounding in their background.

- Introduce them to the chat box and ask them to type their name and a one sentence goal for course. Let them know that this is where they can ask for tech help or ask questions so that they don’t interrupt the flow. Just make sure they know they can chat with individuals or everyone and to default to everyone unless it’s a question they want to keep private.

- Next put up a picture of a map of the US (or wherever most your folks are from) and have them annotate (sticker, drawing, etc) where they’re from. Those from somewhere not on the map can type with the text icon where they’re from. This gets them used to the annotate feature which they can utilize for terrain activities later.

By going through these things on zoom, you get everyone on the same page with zoom tools and etiquette and get to learn a little about the students without taking a bunch of time to have them each introduce themselves.

In Person Making Tour Groups Activity

Provided by: Zack McGill

- When preparing for the classroom space for the day, pass out notecards and write these prompting questions up on the board:

- Notecard:

- Name.

- Who you’re here with (if anyone).

- Travel Equipment (Skis, Split, Snowshoe)

- Backcountry Experience.

- BEGINNER I’ve never (or only a handful of times) toured in the backcountry before.

- INTERMEDIATE I’ve toured a bit and been exposed to a variety of conditions in the backcountry.

- ADVANCED I’m a strong rider with at least a few seasons of experience touring in the backcountry riding a variety of conditions.

- EXPERT Skiing/Riding is life. I tour in the backcountry 60+ days per year and have many years of experience.)

- Prompt folks to complete them while they’re waiting on everyone to arrive.

- Collect these notecards at first break so you can make groups of folks of like ability level (or not) and ensure folks who tour together are placed together.

- Notecard:

Back to Top | Back to AIARE 1 Classroom Activities

Avalanche Problems

There’s tons you can do with avalanche problems that doesn’t involve you flipping through the slide deck. Willie Webster, for instance, before day one in the classroom assigns/volunteers each student an avalanche problem. They can read about it in the back of the blue book and watch some YouTube videos. Then in class they get to describe it, what signs to look for, etc. with the group. Here’s a couple other activities and lesson plans to give you some ideas!

Avalanche Problems Review and ForecasT Activity

Provided by: Dan Sandberg (MSU)

- What is an avalanche? Is any moving snow an avalanche?

- Is every avalanche a concern? What are the hazards? (asphyxiation, trauma)

- What is the value of having these 9 avalanche types defined? Point out specific relevance for why it is important (ex: glide avalanches are almost impossible to forecast, very specific paths and conditions, uncommon, slow moving, glide crack as a “tell”).

- Showcase videos of each avalanche problem, allow for questions. AIARE online course has a good text description of avalanche problems under “Anticipate the Hazard” and includes the “Avalanche Problems Explained” video but no video footage of any of the nine types.

- Discuss the approximate timing and relevant observations/warning signs for each avalanche problem type. Consider using the Avalanche Problem Toolbox graphics around avalanche behavior, remote triggers, and Reliability of tests and observations to supplement your presentation

- Highlight the Avalanche and Observations (A & O) Reference Page as a resource that we will use for tour planning.

- Activity: Use current day’s forecast and 1-2 additional forecasts with a different avalanche problem. Have students:

- Identify any terminology that they don’t understand (i.e. SWE, avalanche danger scale ratings)

- Identify the observations/warning signs that would clue us in to the presence of this avalanche problem on this day. Reference the Avalanche and Observations (A & O) Reference Page: Focus on observations that get at the presence of an avalanche problem rather than its sensitivity/reactivity.

- Identify the avalanche problem(s)

- Identify generally where in the terrain the avalanche problem(s) are most likely to be (you can use the 3D mountain if you’d like)

Avalanche Problems as Animals

Provided by: Zack McGill

Instead of you flipping through the slides and doing the talking, have the students do it for you! This activity splits the students into teams of two-three utilizing the breakout rooms feature for online classroom or just splitting them up however you want in person and have them research a particular avalanche problem to teach to the class.

Here’s the activity:

Room 1: Loose Dry

Room 2: Loose Wet

Room 3: Wind Slab

Room 4: Storm Slab

Room 5: Persistent Slab

Room 6: Wet Slab

Room 7: Cornice Fall

Room 8: Glide

Room 9: Deep Persistent Slab

Directions:

- Introduce yourselves. Choose Speaker (Person responsible for presenting findings to large group). That person types up or writes down answers to questions.

- Use: Avalanche Problems and the A+O resource (Pg. 56-58 in Field Book) to answer these questions:

- If your avalanche problem were an animal, what would it be?

- How/where does it form?

- What does it look like?

- Warning signs? (red flag observations)

3. Come back to main group ready to share.

Students then have 1-2 minutes to teach the rest of the folks about the avalanche problem as you share your screen and show some photos of the particular avalanche problem being discussed. Be sure to make sure they are delivering correct information and jump in as needed to fill in any gaps and clarify points.

Avalanche Problems Sorting Activity

Provided by: Anne St. Claire

This activity is a good one to check for understanding at the end of teaching about avalanche problems if doing an in person classroom session. Pass out notecards with the avalanche problems written on them (if doing all 9, you should have 9 notecards passed out each with one of the 9 avalanche problems written on them). Then pass out other notecards that have the definitions of the avalanche problems written on them. Have students find their partner who has the corresponding notecard (definition or name). Then, once they have their partner, you can have folks sort themselves in several ways to bring out good discussions and make sure folks are understanding. Here’s some suggested sorts.

Sort yourselves from:

- The avalanche problem that is hardest to predict to easiest.

- The most destructive avalanche problem to least destructive.

- The avalanche problem that is longest lasting to shortest lasting.

The Avalanche Problems Spectrum Activity

Provided by: Eric Haskell

Directions:

- Divide students into 8 groups.

- Give access to https://www.avalanche.state.co.us/forecasts/help/avalanche-problems/ or use back of bluebook avalanche problems A+O resource.

- Assign each group a different problem, give time to review problem.

- Go through one spectrum at a time (See below) and have students align themselves on the spectrum, then time for them to talk to neighbors and arrange themselves accordingly, giving time for discussion and explanation of why their problem is where it is, and time for rearranging.

The spectrums are as follows:

- Consequence in terms of size(in general, these types of avalanches are town destroying on one side or would take my chances/small on other).

- Temporal (last all season on one side, last hours to day on other)

- Spatial (last from valley bottom to mtn top, all aspects on one side, very isolated on other)

- Ease of identifying (super obvious on one side and super difficult such as identifying individual snow grains on other)

5. Wrap up activity with each group putting all pieces together to explain how we manage each individual problem (i.e. identify and avoid, give time to heal, etc.)

Considerations:

- No right or wrong answers, but I will ask leading questions if spectrum is wildly skewed or students are not accurate with their explanation.

- Extremes of spectrum are on opposite sides of room and students arrange themselves on spectrum –supposed to be active. Be sure to emphasize the activity is gross generalization and that there are always exceptions.

- Also emphasize that any avalanche problem can be deadly in the wrong circumstances.

Back to Top | Back to AIARE 1 Classroom Activities

Track the Season’s Conditions/Snowpack

Understanding the snowpack as a level one student can be a difficult undertaking on a short three day course. Here’s some activities and lesson plans designed around getting students thinking about layers and interfaces, common snow grains, and everything snowpack.

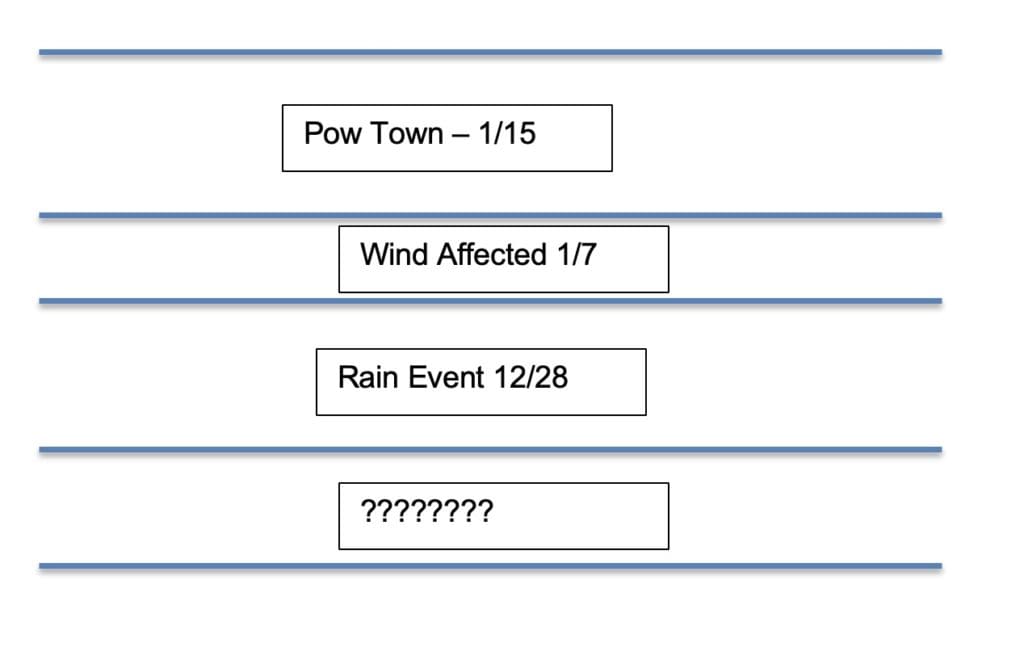

Draw the snowpack activity

Provided by: Nicholas Vincent “Vince”

Turns out, folks in a level 1 usually have trouble differentiating layers and interfaces as well as even just visualizing what different weather events do to the snowpack. This activity is best done either early on in the track the seasons conditions lesson or at the end to check for understanding. We usually use it as a way to establish a baseline and get to gauge what students actually know about snowpack (have they paid attention at all to what’s going on out there at all?) before diving into showing what resources are available to them to inform what’s going on under the snow.

Summary of Activity – Gather information about what has happened this season and draw our CURRENT snowpack on the screen share white board for online or an actual whiteboard or big post its for in person.

Objectives for Online:

- Gather info using only memory and each others experience this season.

- Get a snapshot of the snowpack in the Baker Backcountry (or whatever zone you’re in). Pick notable weather and avalanche events and give them a name, symbol, picture, whatever… Hint: Keep it simple.

- Have a Zoom savvy person share screen and select white board. Draw the seasons snowpack as a team. Include simple grain types, significant weather events and identify avalanche cycles if you can.

- Take a screenshot of the whiteboard.

- Select a person to share screen and describe your summary of the seasons snowpack drawing using the info you just learned about.

Stacking Layers Activity

Provided by: Jason Speer

This activity is geared towards getting students thinking critically about layers and how they can come together to either create a relatively stable or unstable snowpack.

- Divide the class into 2-4 groups (depending on class size – groups of 6 work well).

- Give each group the same stack of layers. For in person classroom, this is best done on notecards or sticky notes that students can manually arrange on a table, wall, or white board. For online-classroom, just have the layers in a shareable document that folks can view.

- Tell 1-2 groups to arrange the layers so that the snowpack on the whole is considered more stable.

- Tell the other 1-2 groups to arrange the layers so that the snowpack on the whole is considered more unstable.

- Come back together after they’ve completed the task and have them share their stacks and explain why they think the snowpack is more stable or unstable in those configurations.

An example of a stack of layers you can provide is as follows:

- 15cm of new, low density snow.

- 5cm thick melt-freeze crust

- 40cm of wet melt forms

- 30cm of dense, wind affected snow.

- 10cm of very faceted snow.

- 50cm of small, compact, rounded grains.

Interactive Snowpack Activity

Provided by: Craig Muderlak

Goals: Foster a more intuitive understanding of snowpack structure and how layer configuration correlate to snowpack stability.

Backlink: Track season’s conditions/weather (red flags), snowpack (hand hardness and layer ID), terrain characteristics that affect snowpack.

Venue: In person – classroom or in the field

Outline:

1) Print out page 1 and 2, cut cards and laminate for use in the classroom or in the field.

2) Hand one “Snowpack” card to each student.

3) Instruct them to create an “unstable” by lining themselves up with one end of the line representing the top of the snowpack and the other end the bottom (discuss)

4) Next, have students rearrange themselves with the same cards to create a “stable” snowpack without adding or removing any cards.

5) Next add 1 card from the “Weather/aspect/terrain” stack and ask groups how this added factor will affect the snowpack/avalanche hazard. Continue to add cards with the same questions. With some of these, there isn’t a straightforward answer. That’s okay. This will elicit discussion and “what if’s” which is good.

6) Allow students to remove or rearrange one card if necessary to create a stable snowpack – or ask what changes in weather or snowpack would be necessary to stabilize the snowpack.

* Considerations: making two groups if there are more than 6 students.

– Additional interactive challenge: One group picks a card from the leftover cards (snowpack or weather/aspect/terrain cards) and strategically places it within the other group’s lineup attempting to tip the “opponent’s” snowpack into a more unstable one. This could be done back and forth between the groups. Can close with asking groups what it would take to stabilize their snowpack.

– Variations – adjust card titles to match the group. Simpler cards for AIARE 1 and more complex for AIARE L2.

| Near Surface Facets1cm4 Finger hardness | Basil Facets (Depth Hoar)10 cm | Surface Hoar5mm grains |

| Graupel1cm | Rounded grains30 cmPencil hardness | Sun crust1 cmPencil Harness |

| wind slab5cm1 finger hardness | Ice layer5 cm | rounded grains30 cm4 finger hardness |

| moist storm snow15 cm4 finger hardness | light/dry storm snow30 cmfist hardness | Rounds50 cm4 finger hardness |

| Facets10 cmFist hardness | Rain Crust1 cmPencil Harness | Melt Freeze Crust10 cmKnife Hardness (AM) |

Weather/Aspect/ Terrain

| Sunny | 38 degree Slope | Shady Aspect |

| Solar Aspect | TemperatureOvernight low 25 degree F, daytime high 40 degree F | TemperatureHigh of 15 degree F |

| Cloudy/overcast | WindModerate (20mph) | Snowing4 cm per hour |

| RainHeavy | 25 degree slope | SnowLess than 1 cm /hr |

| Freezing RainLight | Temperature34 degree F temp | WindLight (10mph) |

Snowpack Art Project

Provided by: Kenzie Carson

Goals:

Connect tracking the season’s conditions via a snow and wx log to identify where problem layers may exist.

Materials:

Large pieces of paper like flip chart paper, markers, colored pencils or pens

Outline:

- Break class into groups of 2-3

- Give the group weather history to build a snowpack such as:

October: 6-8” fell

Late Oct: Dry cold spell

Nov: 12” fell with cold temps

Mid Nov: Sunny and warm conditions

Late Nov: 2-4” fell every day for three days

Early Dec: Clear, Cold, Calm nights

Mid Dec: 2’ of snow fell over four days

- Have each group draw out the season’s snowpack

- Have them Identify the following:

- Where would you anticipate hard over weak layers?

- Which interface are you most concerned about?

- What do you think the current avalanche problem may be?

- If you went for a shralp in mid December, what would the conditions be like? Pow town? Firm fun? Bullet proof…. Etc.

- What would this snowpack need to become more stable?

- Can have each team do a show-and-tell presentation and compare what each team got.

- How did each group interpret the wx events differently or similarly?

Allow for some time for them to discuss why they think different weather events would produce the layers and interfaces they drew.

Snow Slang Activity

Provided by: AIARE Instructor Manual.

You know more about snow than you realize!

- Have the Participants break up into groups of 2-3. Write down as many names for snow as they can come up with. NO SCIENTIFIC NAMES!

- Think of the best snow day of your life. What was the snow like? What was the weather like that led to that snow?

- Think of the worst snow day of your life. What was the snow like? What was the weather like that led to that snow?

- So just with these personal anecdotal stories, we instinctively know that not all snow days are equal. With each storm, the snow falls out of the sky at different rates and different times, with different winds, temps, etc. We also know that snow changes over time for better or worse.

Snowpack Exercise

Provided by: Chris Pruden

Goals: Increase student understanding of how different wx factors influence and change the snowpack. Make a connection to how changing snowpack factors can influence terrain mindset.

Materials:

Boards with velcro and colored velcro strips to build snowpack with different colors

Outline:

Cooler colors are softer layers of the snow

Hotter colors are harder layers of the snow

-Thickness of layers is just for relative comparison and does not have to be perfect

-For each weather situation, build a snowpack based on what you have learned

After building a snowpack decide as a group what your mindset would be for a day of touring:

-Avoid avalanche terrain – feeling sketchy.

-Limit exposure- there are safer places in the terrain, but also areas of danger.

-Step out cautiously – most areas are unlikely to hold avalanche danger but avalanche risk does exist.

And what is your major avalanche problem? (Recall the previous presentation)

First Weather Situation

-It’s been a slow start to the winter and there is just 4 inches of snow on the ground from early storms. The temperatures have been very cold through the fall. Just yesterday though, a huge storm rolled in and dumped 18 inches of snow with moderate winds.

Second Weather Situation

-It’s mid winter and there is a solid base of settled snow with not much variation. It has been super warm the last couple of days but cold weather arrives for a day followed by 2 inches of snow the next. After this small storm it stays very cold and dry for a week. After this dry period, a large snow storm moves through the area but with very little wind depositing 12 inches of storm snow.

Third Weather Situation

-It’s mid winter and it just snowed 8 inches on top of a relatively settled and uniform snowpack. Overnight, the wind blew 80 mph from the SW.

- What would the pack look like on the NE and E slopes?

- What would the pack look like on the SW and W slopes?

Back to Top | Back to AIARE 1 Classroom Activities

Human Factor

Kind of what it’s all about! How we as humans make decisions. These activities help students gain awareness over their own decision making processes and the language to be able to discuss heuristics together and come up with productive solutions.

FACETS and You

Provided by: Zack McGill

This activity is designed to get folks talking in their field groups about common heuristic traps and have them identify some that they are most susceptible to. It’s good to do this after talking about some of the common heuristic traps out there so that folks have a common language to refer to them by. Hopefully by talking about them before heading out into the field, they will be more on everyone’s radar and folks have the language to call out others when they see them coming into play. In this example I just used FACETS since that is a common acronym folks tend to use nowadays to help students remember them.

FACETS

Familiarity

Acceptance

Commitment

Expert Halo

Tracks on the slope

Scarcity – “Mad Pow”

You can get definitions of each of these HERE.

- Which of the human factor traps do you find the most dangerous?

- What human factor traps are you most susceptible to?

- How can you avoid letting them influence your decision making?

- What are some positive characteristics you look for in backcountry partners?

- Anyone have a good story of the human factor at play? Doesn’t need to be skiing related.

Relay Recall

Provided by: Eric Haskell

Half the world is composed of people who have something to say and can’t, and the other half

who have nothing to say and keep on saying it.

-Robert Frost

Often we attribute critical errors resulting in avalanche incidents to communication breakdowns; yet we spend the least amount of time practicing communication in staff training and avalanche courses compared with other skills.

Putting thoughts into words and having others understand exactly what you are trying to convey can be a hard to impossible task. Even when it is easy we often fail to communicate. Sharing our observations, our risk assessment and our plan is something that should come out seamlessly as professionals. It is something that most of us could improve upon. We should also teach recreationalists to communicate well. The basics of how to do this are well known yet get skipped in the field. Practice makes habit and what follows are some tools to practice.

These simple and effective tools were developed by the military. They have been adopted in healthcare and emergency services to avoid errors in dynamic high-risk environments where communication is critical – sounds familiar? Research has shown the use of these tools results in higher team performance and a dramatic decrease in patient errors in healthcare. They are easy to use and ensure all of the important information is conveyed. Two of these tools are SBAR and closed loop communication.

SBAR is an acronym that creates a template for organizing our thoughts and conveying them to our team.

Situation – What was observed? What is happening?

Background – What is the context?

Assessment – What is the relevance? How does this speak to stability?

Recommendation – What are we going to do about?

In addition to SBAR, closed loop communication creates a circuit that ensures our message has been transmitted without error. It involves call-outs and check-backs. A call-out is a message that is directed to a specific individual whom the message is relevant to or to the team, and calls for a response.

Call out: “Hand shears and test slopes are consistently showing clean, easy results on a surface hoar layer 30cm down. This seems to be at the interface of the last storm. Skier triggered slides will be easy to trigger and small to large in size from this layer. Let’s close Jerry’s Bowl and Poker Face and use caution on the small terrain features on Rolly Bowl.”

Check back: “You found surface hoar 30 cm down at the interface of last storm. It is producing clean, easy results and could result in small to large avalanches that are very sensitive. You want to close Jerry’s Bowl and Poker Face and exercise caution on Rolly Bowl. What about Ricki’s?”

These concepts are easy enough in theory but require practice to become habit. Here’s an activity to practice!

- Divide group into teams of four or more.

- The first team member has one minute to read Statement A and then must whisper, from memory, to participant # 2.

- #2 tells #3, #3 tells #4. At the end check for accuracy.

- Round two, the group uses call backs at each transmission before telling the next participant statement B.

- Compare the results. Discuss what other techniques would aid in accuracy such as a field book. Were the most important components of the message conveyed or lost in the details?

Statement A: “At 9700’ on an NE slope I found fist hard 1-2mm facets 87cm down, sandwiched between a pencil hard crust and 1 finger facets. The layer was reactive with moderate, sudden planar CT and ECTP21. This is the layer that failed on Mount Diamond’s east face yesterday, HS-N-R3-D3.”

Statement B: “Yesterday, two slides were observed on the west side of Buck’s Drainage. They were SS-AM-R2-D2 and SS-AS-R1-D1.5. Both slides failed on 6mm surface hoar buried 42 cm deep. If tonight’s forecast of 16 inches comes to fruition, this could step down to the widespread 3mm depth hoar layer that has been lingering since Oct. 28th.”

Human Factor Assignments

Provided by: William “Willie” Webster

At the end of day 1, I assign/ volunteer every student a human factor. On day two they share an example of how that human factor has affected their decision making. The example doesn’t need to be related to backcountry travel, but as a group we can come up with scenarios where it could. The stories are pretty amazing, and by day two the group is comfortable sharing some interesting and sometimes vulnerable stories.

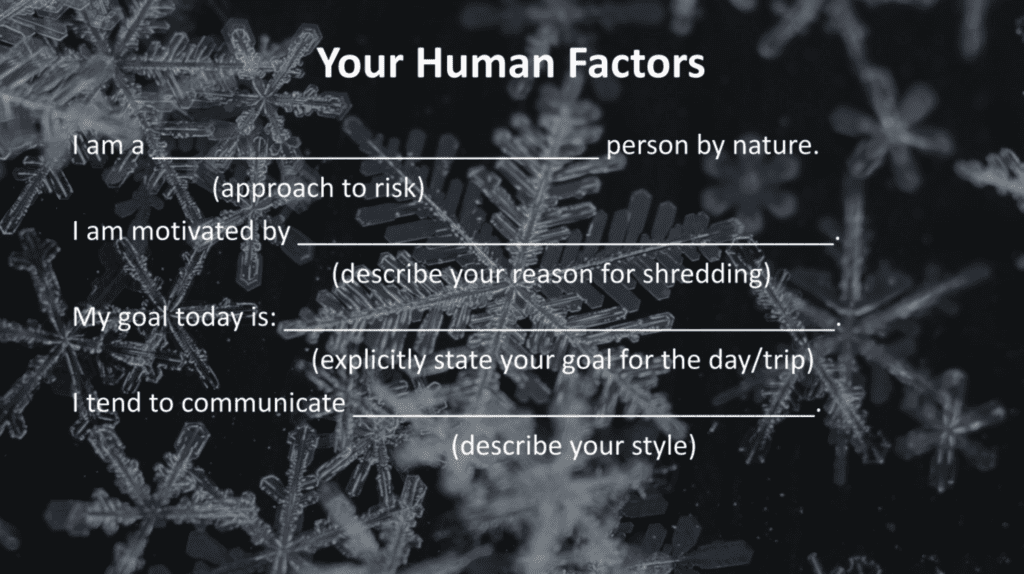

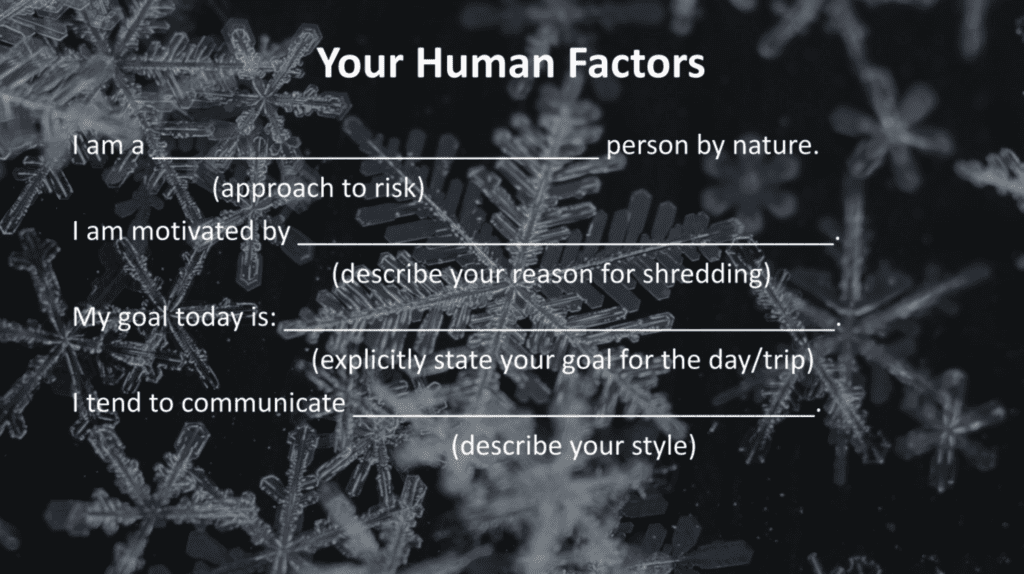

Human Factor Madlibs

Provided by: Sara Boilen

A really nice culmination activity for assembling the group is to have students answer and then share their own Human Factor Madlibs.

After students complete their Mad Libs:

- Have them look at Assemble Your Group Checklist and discuss what would be helpful/relevant from their Mad libs to communicate with their team members or be mindful of for themselves.

- If students have already done their Risk Tolerance Questionnaire, prompt them to add their realizations from that questionnaire to this conversation. You can find the Risk Tolerance Questionnaire under the Risk Tolerance heading below.

- After completing the Assemble Your Group Checklist conversation, highlight that personal motivations and risk tolerance change over time and can be influenced by many different factors on any given day, season or year.

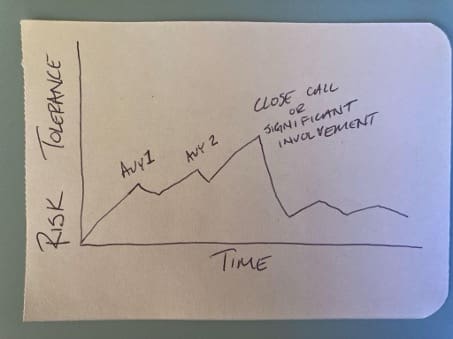

- If time allows, draw a personal risk tolerance over time graph to illustrate how our goals, motivations and risk tolerance change over time:

- Highlight the importance of using checklists to combat human factors.

- Wrap up by encouraging folks to keep their Mad libs and revisit it over time and use as a tool to inform conversations with their partners.

Assemble Your Group Checklist – Real World Conversations

Provided by: Kenzie Carson

LEARNING OUTCOMES:

● Students will get an example of what conversations may look like working through the Assemble your Group Checklist

● Students will practice mock conversations with their peers to become more familiar with this process.

MATERIALS NEEDED: This slide deck. You have multiple options with this lesson, you could run through the slides if you’re running low on time or print them out as scripts and you and another instructor act out each part of the checklist.

INTRODUCTION:

This lesson is intended to give examples of what these bullet point prompts can look like in real conversations with your touring partners.

PRACTICE/ACTIVITY:

● Run through the slide deck

OR

● Print content of slide deck and have two instructors act out the the examples

● Split groups into 2-4

● Have students refer to Pg 2 for the prompts, each student takes a prompt and facilitates the conversation for that prompt. Ex student #1 has “Compatible Goals” What are some questions you will need to ask your partners to see if you have compatible goals?

● Can put these questions up on the whiteboard to help students come up with questions or ideas of how to have these conversations

○ What are your goals for today?

○ Given the avalanche forecast, what type of terrain are you comfortable with today?

○ Are you comfortable with honoring the most conservative voice once we’re in the mountains? And maintaining a pace where everyone can be included in conversations?

○ Given our objective and the conditions, what is the optimal number of folks for this tour?

○ How are you doing physically and mentally today? Anything that may be distracting for you?

Risk Tolerance Cards

Provided by: Sarah Ebright

LEARNING OUTCOMES:

-Increase understanding of components of risk and how they connect to managing risk with avalanches

-Increase individual awareness and self reflection of personal risk tolerance.

MATERIALS NEEDED: Risk Cards (below)

INTRO:

● Human beings are susceptible to many different forms of risk in our lives. If folks can remember their driver’s education, the instructor likey talked about the risk involved with operating a motor vehicle. Similarly, risk is often talked about in business and finance. If investors or business owners never engage with risk, there will likely be no or limited gains. Risk tolerance is the term used in most industries to define how much risk an individual, business, financial institution, etc is willing to take on. Often, the more risk X accepts, the more vulnerable X becomes to consequences.

● Go through this Slide Deck

● Notes for Slide Deck:

○ Seinfeld clip – is anyone a risk management expert?

○ Show of hands: What’s riskier? DRIVING, DRIVING YOUR CHILD, LIGHTNING STRIKE

○ The concept of risk is vague and not always intuitive. As humans, we don’t always look at situations logically, so we’re going to break it down.

○ The Risk Equation involves 4 things: let’s define each one… (shout it out!)

■ Probability – What are the chances something is going to happen?

■ Consequence – What would happen?

■ Vulnerability – How susceptible am I to the impacts of the hazard?

■ Exposure – How am I interacting with the hazard?

○ Let’s use the example of getting in an accident while driving:

■ Probability – Am I in Kathmandu or Three Forks?

■ Consequence – Are the vehicles going 15mph or 80mph?

■ Vulnerability – Am I driving a Dodge Ram 3500 or Smartcar?

■ Exposure – Am I driving in rush hour or at 3am?

PRACTICE/ACTIVITY:

● Have students group together in groups of 2-3

● Hand out cards with statements – categorize each. Find the cards here.

○ Probability

■ There’s a 30% chance of rain today

■ The ice on the skating pond is only 1/8” thick and it’s 45 degrees out

■ Only a quarter of all applicants get into Harvard

○ Consequence

■ Seafood causes me to break out in hives

■ Breaking your arm in a mountain bike crash

■ Topping my rain boots in the river

○ Vulnerability

■ My car doesn’t have snow tires on yet

■ Wearing a sunshirt and long pants on a sunny day

■ I forgot to bring my cup to my hockey game

○ Exposure

■ Working from home today instead of driving on icy roads

■ Sticking to in-bounds ski terrain

■ Drinking only bottled water in Mexico

● Can you chat in small groups and come up with an example of Probability, Consequence, Vulnerability, and Exposure in an avalanche context? (Hint, check out the Risk Management Framework on page 1 of your blue book)

● So in terms of avalanche terrain, what do we have control over?

○ Vulnerability and Exposure

● How do we limit our vulnerability and exposure? Using the Risk Management Framework in the blue book!

○ How to reduce vulnerability

■ Wear beacon, shovel, probe

■ Wear an airbag

■ Wear a helmet

■ Limit exposure

○ How to limit exposure

■ Choosing the right terrain

■ Avoiding being above terrain traps

● Optional: Show personal risk tolerance over time graph.

● Takeaway:

○ Start thinking about personal risk tolerance and whether your choices are in alignment with your stated risk tolerance.

○ Reading and reviewing case studies or accident reports and connecting emotionally with other people’s accidents can help us learn without having to make a costly mistake ourselves.

● What questions do you have?

Backcountry Ski Risk Tolerance Questionnaire

Provided by: Jediah Porter. Adapted by: Kenzie Carson

NOTE: This activity can be used in conjunction with the Sara Boilen Mad Libs activity. I recommend you start with this questionnaire when teaching Risk Management / Risk Tolerance and incorporate the learnings gleaned from this questionnaire when introducing Mad Libs during the Teamwork/Assemble Your Group Lessons.

LEARNING OUTCOMES:

-Increase individual awareness and self reflection of personal risk tolerance.

MATERIALS NEEDED:

Questions listed below. Could put up a projector or print out so each student has a copy to take with them.

INTRO:

● Human beings are susceptible to many different forms of risk in our lives. If folks can remember their driver’s education, the instructor likey talked about the risk involved with operating a motor vehicle. “77% of motorists in the US have been in at least one accident in their lifetime.” Many accept this risk because the reward or travel, getting to school, work, etc is great. Similarly, risk is often talked about in business and finance. If investors or business owners never engage with risk, there will likely be no or limited gains. Often, the more risk X accepts, the more vulnerable X becomes to consequences.

“Risks and rewards are intertwined, to put it mildly. When the reward is great(sic), what are you willing to put on the line?”

-Jediah Porter

● Can use this graph to refresh previous learning:

● Speak to how to lower likelihood of getting buried (risk tx = airbag) and how to lower likelihood of consequence of getting buried; risk tx = carrying B/S/P and practicing rescue with your team often.

● In the Assemble Your Group section of pg 2 of the blue book it prompts you to discuss your risk tolerance. This activity is designed to help you gain clarity of your personal risk tolerance to help inform this valuable conversation with your peers, partners and family.

PRACTICE/ACTIVITY:

– Give copies of printed out questionnaire to each student or put questionnaire on projector

– Have each student fill out questionnaire individually:

Backcountry Ski Risk Tolerance Questionnaire

- In general, how would your best friend describe your recreational risk taking tendencies?

○ A go-getter

○ Willing to shoulder some risk with research

○ Cautious

○ Risk avoider

- You have professional level guidance and information, but total freedom to choose where you go. In any situation, an avalanche has a 15% chance of badly injuring you and a 10% chance of killing you. What would you pick?

○ Crusty, horrible snow that absolutely will not avalanche.

○ Smooth hard snow that has a 5% chance of avalanching.

○ Boot-top powder that has a 15% chance of avalanching.

○ Movie-worthy face shots with a 25% chance of avalanching.

- When you think of the word “risk” which of the following words comes to mind first?

○ Loss

○ Uncertainty

○ Opportunity

○ Thrill

- You are packing for a day in the mountains. Your backpack is nearly full. Do you (and you can only fit one):

○ Bring another liter of water and ski an extra run

○ Bring your emergency shelter in case something bad happens

○ Bring the bigger camera to better capture the experience

○ Bring a seat cushion and a thermos of tea for an hour of summit serenity

- It is day 9 of your 12 day expedition to Peak XYZ. You stand on the summit with three descent options. Any one of the choices will take the remainder of your time on this long-anticipated dream trip. Which do you choose?

○ Your ascent route. With wind-scoured conditions, boot tracks, and a line of others ascending. Little to no avalanche hazard and minimal slip and fall hazard.

○ The 35 degree powder couloir with minimal slip and fall hazard and about a 5% chance of a really bad avalanche.

○ The 50 degree “money line” with perfect snow, certain death if you fall, and about a 5% chance of a really bad avalanche.

- Mountaineers, on foot, rope up for nearly all glacier travel. The rope reduces or eliminates the consequences of a fall into an unseen crevasse. In the exact same conditions and terrain, ski mountaineers rarely descend roped together. A crevasse fall is slightly less likely on skis than on foot, but the consequences of an unroped fall into an unseen crevasse are dire.

○ “Going onto glaciers at all is preposterous”

○ “It is a cool-looking environment. I could see going there, but taking all the precautions, regardless of my mode of travel”.

○ “Skiing downhill roped to my buddy seems annoying, but better than the alternative”.

○ “I need a damn good reason to compromise the enjoyment of my skiing. I’ll gladly ski unroped on those glaciers”.

- Each morning you get an emailed avalanche advisory and a screen full of ski stoke. Today is your day to shred. The advisory says that, on your favorite type of terrain, human triggered avalanches are possible. Reports indicate that your favorite type of terrain will be untracked, sunny, and perfect snow. Do you?

○ Stay home

○ Go to less enjoyable but lower likelihood terrain

○ “Possible” isn’t “for sure”. Go to that untracked, sunny, perfect spot.

- You most admire/seek to emulate/wish to be:

○ The 75 year old you’ve never heard of that has ridden the same “Hippie Trees” for 50 years

○ The 40 year old quiet crusher that has 20 years of perfect snow, an occasional expedition, and a handful of close calls

○ The 30 year old magazine star with a dozen first descents, roving and growing resume of amazing imagery and experiences, a deceased close ski partner, and annual (or more) big mountain incidents/close calls.

● After folks have finished, draw a personal risk tolerance over time graph on a whiteboard to illustrate that risk tolerance is not stagnant and may change over time and experience. ADD into bluebook Pg2: What is your risk tolerance today?

● On the same piece of paper as the questionnaire, have students draw their current risk tolerance over time graph.

○ Where are you at right now in your Backcountry schralping experience?

○ Do you think your backcountry actions are in alignment with your stated risk tolerance?

○ Take this paper with you, consider storing it in your bluebook to guide conversations with partners and return to the questionnaire to help you recalibrate your understanding of your risk tolerance as it changes over time.

Powder Arousal Activity

Provided by: Zack McGill

If you haven’t gone through a deep dive of the White Heat Project… treat yourself. Thanks for sharing this with me, Jules! It’s all geared towards understanding why folks make risky decisions in the backcountry. One point of research you’ll find there is where researchers compare sexual risk taking to backcountry powder skiing. You can watch a short video on what they coin “powder arousal” HERE as it is the impetus for this activity.

Have students answer these questions on a scale of 1 to 7 where 1 is Absolutely not and 7 is Yes, absolutely:

- Would you…

- feel frustrated if your ski partner is scared and refuses to ski an out of bounds run that you want to ski?

- try to persuade a ski partner to ski an out of bounds run that you want to ski is he/she is nervous and says no?

- leave your partner out of bounds to go ski a run if he or she is nervous and says no?

2. It’s a blower pow day. Can you imagine riding in the backcountry…

- if you forgot your avalanche beacon but the danger was moderate?

- with someone else who forgot their avalanche beacon but the danger was moderate?

- alone with the appropriate avalanche gear when the avalanche danger is moderate?

- with a partner who’s backcountry travel skills are unknown to you when the avalanche danger is considerable?

- with a partner with the appropriate avalanche gear including avalanche backpack when the avalanche danger is high?

After folks work their way through the sheet, ask if anyone put over a 4 for any of the questions. Likely the answer is no, but could lead to some good discussion if someone actually does.

3. Ask the class how they think their numbers would change if they weren’t sitting here in an avalanche class but were standing at the top of a lift line on a beautiful powder day and they were faced with the same questions?

Introduce the term “Powder Arousal” and have them watch from 4:44-6:44 in the Powder Arousal Video. Use this discussion to segue into your presentation on how humans make decisions and common heuristic traps.

Back to Top | Back to AIARE 1 Classroom Activities

Avalanche Terrain

These activities are designed to get students engaging with avalanche terrain. From simply identifying avalanche terrain, to actually figuring out the best ways to move through it based on conditions, these are some of the most important lessons we can give to students.

Avalanche Terrain ID Activity

Provided by: Zack McGill

This activity is designed to get folks immediately putting into practice what they learned during the avalanche terrain lesson. It has students look at photos of terrain in their venue (you’ll see that the photos provided are from the Baker Backcountry but you can just insert your own) and then think critically about what hazards are present and how they would move through that terrain. The activity is great for in person as well as online classroom. Descriptions of both are below.

Activity Description for Online Classroom:

Choose Speaker (Person responsible for presenting findings to large group). That person shares screen and opens up ONE of the terrain photos from HERE. Or wherever your venue is.

As a crew:

- Put stamps on at least three trigger points.

- Draw an up-track that most keeps you out of avalanche terrain.

- Circle at least three terrain traps.

- Speaker takes screenshot.

- Share with whole group once back.

Activity Description for In-Person Classroom:

For in person classroom, it’s great to have a terrain photo with corresponding Topo map with slope angle shading to that terrain printed back to back and laminated. This way, folks can use dry erase markers to complete the same steps as above.

Route FInding Exercises

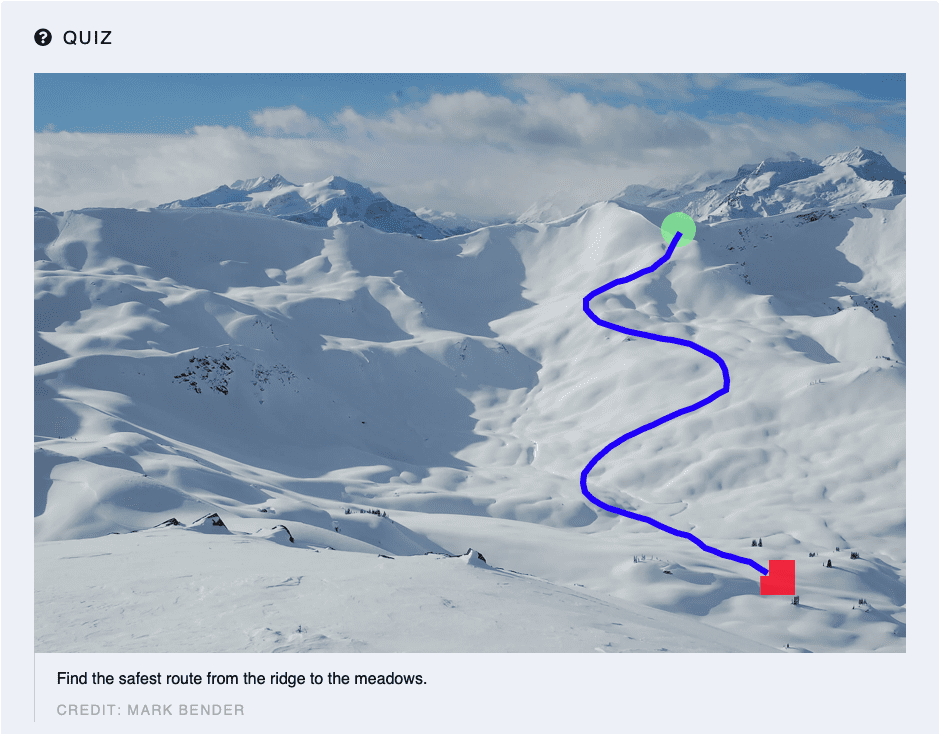

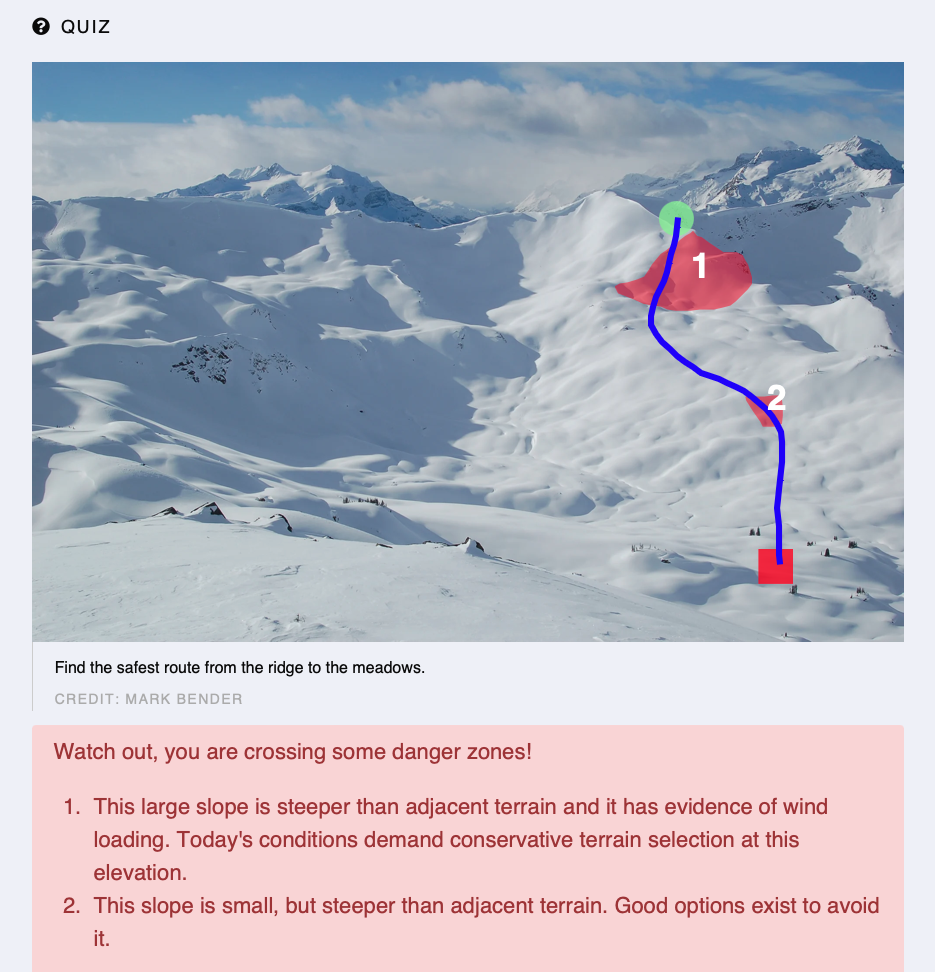

Provided by: John Barkhausen

Useful for either in-person, online, or a link for continuing education after course is the Avalanche Canada Route Finding Exercises: HERE.

You can have students take turns trying to find their way through the terrain utilizing the safest route and avoiding avalanche terrain. There are multiple right answers for every terrain photo and so many wrong ones! If students do enter avalanche terrain, helpful hints as to why are shown.

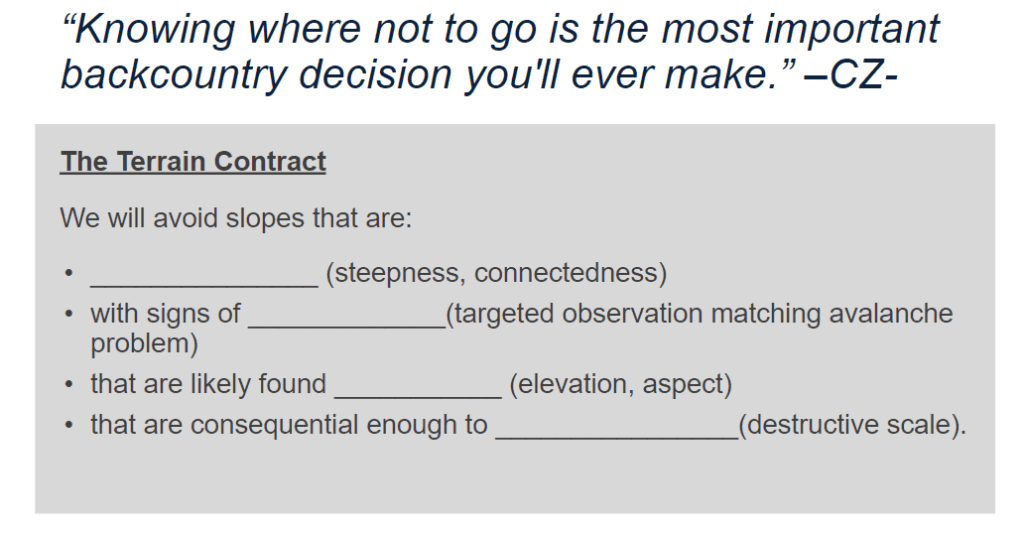

THE TERRAIN CONTRACT

Provided by: Anne St. Clair

Observations and Decision Making

Provided by: Eric Haskell

- Divide group into small groups of four to five.

- Each group is provided with a map of the terrain they will be “traveling” through with four routes on it and a set of cards (enough for each participant to have five to six cards.)

- All routes travel through avalanche terrain – complexity of terrain should be matched with appropriate challenge of group.

- On each card is a clue pertaining to parts of the avalanche forecast, weather forecast, recent field observations, group equipment and team components (such as who is part of the team and who is hung over.)

- Conditions should coincide with a moderate hazard rating with weather pushing to considerable as the team is in the field.

- The cards will be evenly distributed. Each participant can read their cards and only their cards.

- After being briefed of the situation and reading their cards, the participants will have 15 minutes to discuss the routes and rank them from least hazardous to most hazardous based on current conditions.

- Participants cannot read from their cards; they can only share the clues from memory.

- While the group is sharing their clues a powerpoint will be playing in the background with additional clues – updated weather forecast, updated field observations from the group as they travel through terrain and photos of observations they would see.

- At the end of the session, compare rankings of the different groups and discuss the correct answer, checking to see if any clues were missed. Discuss how clues are missed while in the real world, especially due to communication breakdown.

Back to Top | Back to AIARE 1 Classroom Activities

Level 1 Field

This section goes into some activities and suggestions for the Level 1 field days. You’ll want to mix and match activities to ensure that folks aren’t standing around too much — especially if it’s stormy or cold out.

Avalanche Rescue | Ride Safely | Tour Day | Snowpit | Debrief

Avalanche Rescue

Typically, avalanche rescue is first on the agenda for your field day. Here are a few activities to get folks going on avalanche rescue.

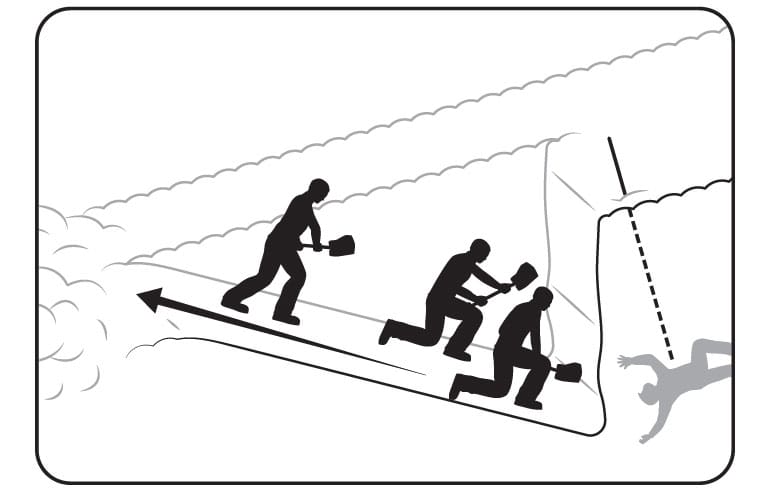

SHovel Drill Activity

Provided by: Julie Ann Holder

Have students practice strategic shoveling with a twist! Ask them how many people they typically ride with. Whatever they tell you is their most common group size is the number of people they get to dig with.

- Students dig down 1-1.5 meters to about the average burial depth in an avalanche while being timed by the instructor. Offer little to know feedback on form unless students are shoveling in a way that will hurt themselves or others.

- After everyone finishes, talk through the times and link to how long folks have under the snow before they die of asphyxiation. This should drive home that getting caught in an avalanche isn’t awesome and the likelihood of being able to rescue someone caught in a big avalanche successfully is tough.

- Segway this talk into a discussion on best group size.

If you want some ideas on strategic shoveling techniques, check out this Strategic Shoveling Techniques resource.

This or That? Strategic Shoveling

Provided by: Devon Schoos

To begin to teach strategic shoveling to students, you can establish the importance of being strategic by demoing two different methods for shoveling and then ask, “which is better? This? Or that?

Examples of things to show:

- Shoveling standing up (this) shoveling from knees (that)

- Shoveling with shovel handle collapsed (this) shoveling with shovel handle extended (that)

- Chopping and mopping (this) only mopping (that)

- Shovel in hoe mode (this) shovel in standard assembly (that)

- Shoveling slowly (this) shoveling quickly (that)

- Digging directly on top of the probe (this) one step downhill (that)

You can also make it more engaging by getting two student volunteers to demo the methods with you telling them what to do at two different stations and the rest of the folks saying which method they think is better.

Provided by: Zack McGill

Probe and Shovels Race

Provided by: Zack McGill

At the trailhead during your trailhead check, you’ll need to get eyes on everyone’s avalanche safety gear anyway, so this activity is perfect for not only checking that box, but getting folks moving and getting acquainted with their gear.

- Have folks fully strapped in ready to tour with backpacks on.

- Tell them that on the count of 3, they will need to drop their packs, get out their probe and shovel, fully deploy each, and put them in the snow in front of themselves. They will be timed.

- After folks figure it out (feel free to stop some folks early if they can’t figure out how to put together their probe) talk about differences in probes and shovels and demonstrate how to deploy both efficiently. Make sure to talk about backcountry touring specific backpacks and the importance of storage of probes and shovels inside backpacks and not on the outside! Oh… and tell them to leave those probe bags at home!

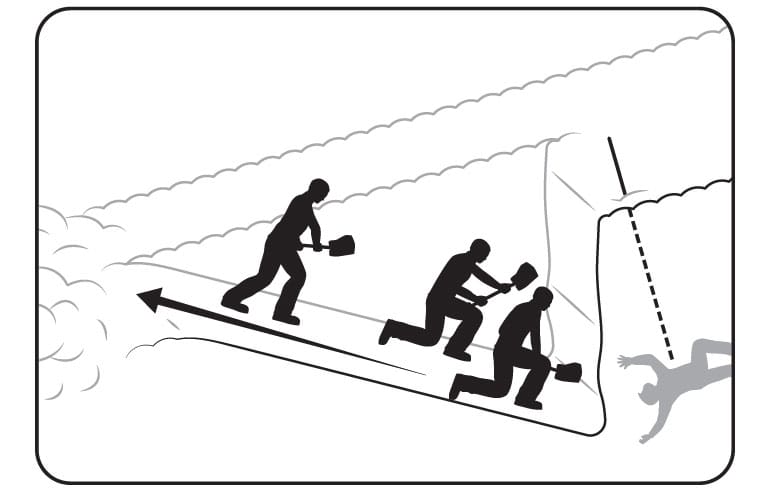

SHOVELING IN THE MODERN ERA

Provided by: Alexis Alloway

After hammering on the need for a “Shovel Master” to take charge of the operation and give clear, concise instructions, I’ll use an acronym to help highlight the important concepts of shoveling in a memorable framework. I love the ABCD acronym that Bruce Edgerly first presented with strategic shoveling years ago. Here is how I’ve updated his original ABCD to reflect current best practices.

I want to teach a technique that works whether you are a solo rescuer or whether you have six people available to shovel.

A. AIRWAY – STAY OFF IT!

Get downhill of the probe strike and don’t collapse the air pocket by walking on top of the snow there the probe strike is.

B. Begin close to the probe.

The number one thing I took home from ISSW this year is that we do NOT want to start shoveling 1.5-2x the probe depth away from the probe. The latest research has shown that if you start from 1.5x the probe depth away, it will increase the excavation time to reach the airway by 2.5 minutes on average (decreasing survivability by 7%). Dig close! How close? For every meter of burial depth, position the lead shoveler one “normal” (not “giant”) step downhill of the probe.

C. Clear to the sides, then Conveyor.

As someone who has dug A LOT of deep holes in the snow, I cannot emphasize enough the importance of clearing to the sides first so that you don’t get walled in behind you and so that you maximize the number of snow blocks that must be shoveled only one time. However, at some point it becomes difficult to shovel to the sides, and if you still have snow to clear, that’s when you are going to have to conveyor that snow behind you. When shoveling in a team, be sure to loudly announce “Conveyor!” when you switch so that people behind you are ready for blocks of snow to suddenly start coming their way.

D. Dig fast.

We want to highlight the need to dig as fast as you can sustain. Maximum effort will burn most people out very quickly, so I tell people to aim for around 70% of their maximum effort.

E. Exchange positions.

Rotations definitely help the people in front get a break. I’ve seen that rotating every one to two minutes is pretty realistic. Your Shovel Master can announce the rotations (and it’s very important they instruct people on how to reposition each time before you start shoveling).

Once I have gone over these big-picture ABCDE principles with my students, the next thing to address is shoveler positioning. If I have more than one shoveler, I strongly prefer to put two people side-by-side up front near the probe. There are two reasons for this.

First, having two people up front means that we are likely to get to the airway faster. If there is only one person up front and they discover a foot while excavating, it’s now going to take some time to get to the head, whereas if there is someone next to them you have more margin to adapt and get to the head quicker.

Secondly, once I get to an airway, I need a workable platform in the snow in order to pull that person out and clear their airway and begin CPR. I’m going to get to that workable platform much faster if we started with two shovelers up front rather than one.

Probe Technique

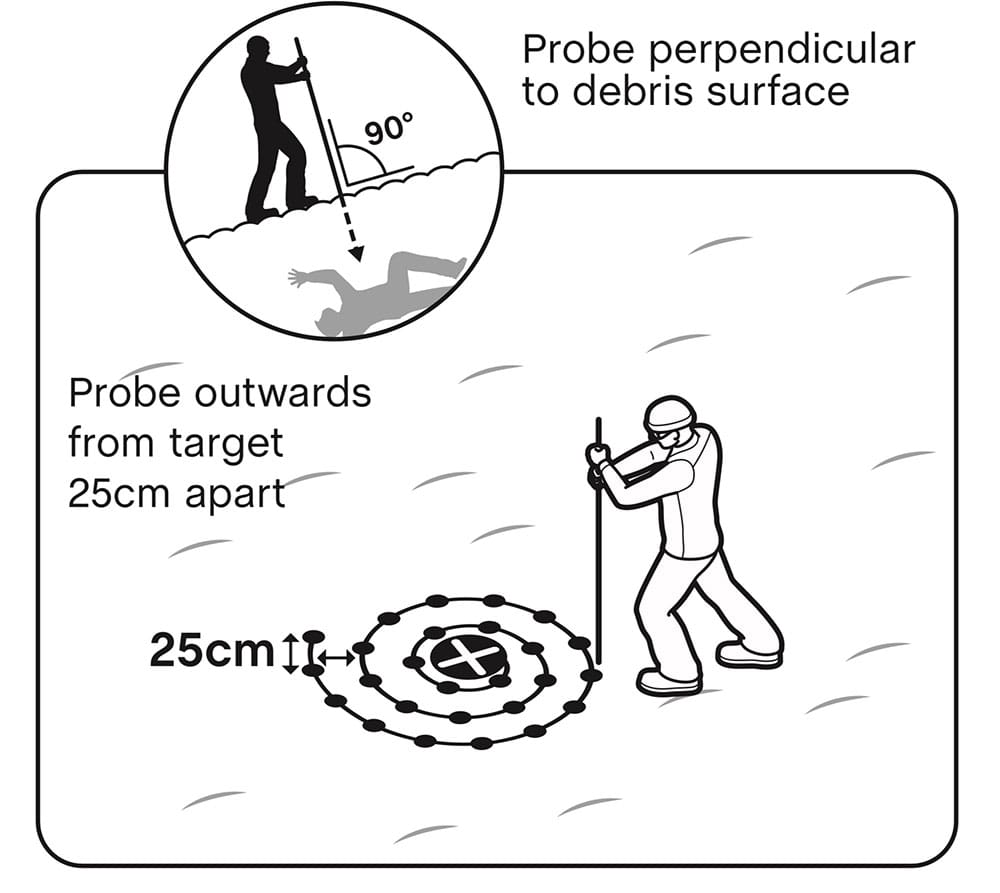

Provided by: Zack McGill

Students have a hard time with probing, so a demonstration of why it’s important is prudent before setting them loose to practice on their own.

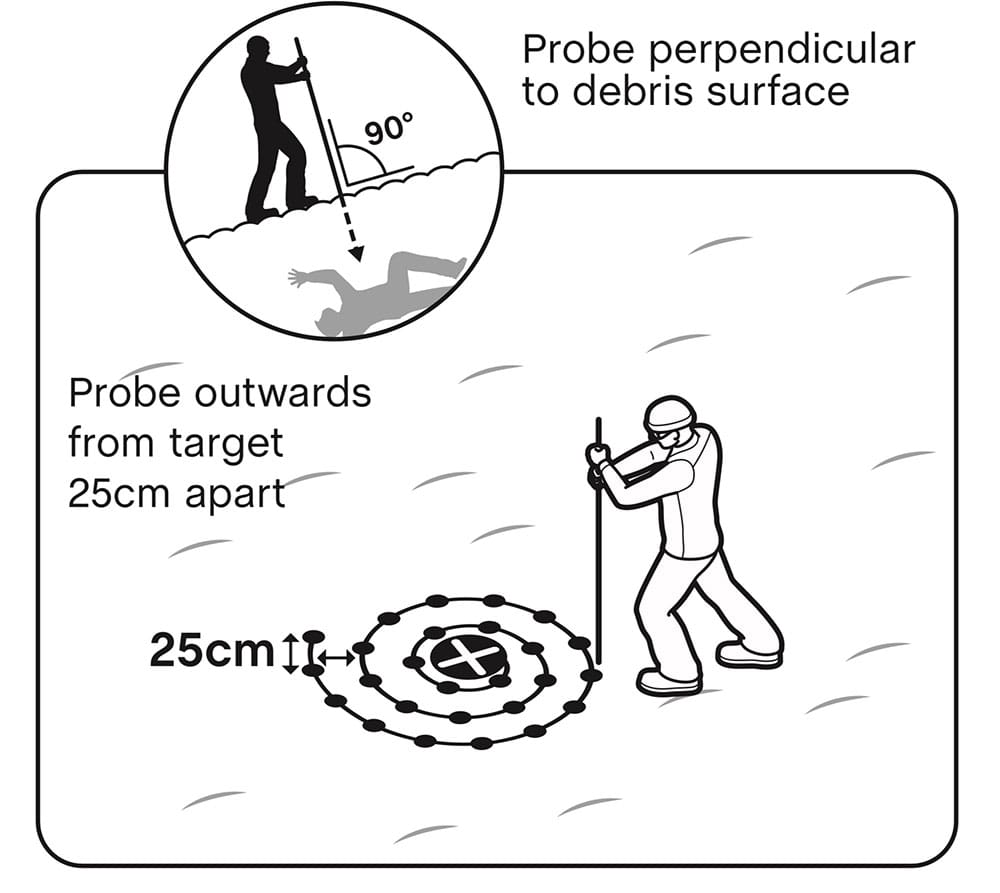

- Point folks to the diagram in the field book showing good probing technique:

- Then have a student lie down in the snow (as long as it’s not too stormy, use a backpack if folks are cold).

- Stand over them with a probe and show how even the slightest difference in angle at the surface causes problems in deep burials as you can miss the buried human even if keeping to the spiral pattern.

The Art of Probing

Provided by: Karin Pocock. Adapted by: Kenzie Carson

Note:

This activity can be used as a way to teach probing or as a course correction for ineffective probing.

Set Up:

-Gather students together and demonstrate how to mark out a 1m x 1m x 1m x 1m box with a probe in an undisturbed patch of snow.

-Have each student find an undisturbed patch of snow to mark out their own box

-Tell students they will have an undisclosed amount of time to probe from the center of their square out to the edges. The goal is to make their probe strike holes as precise, perfect and even pretty as they can. At the end we’ll go on an art walk and decide which box looks the best!

Practice:

–Set a timer for 1 min, don’t tell students they only have 1 min.

-Stop them after 1 min, walk around and discuss with students what was hard or easy about the goals of a “perfect box,” see who was able to probe the whole box. (Many students will successfully probe 1m box in 1min)

-Use this as an example that taking your time to do precise, methodical probing will save time.

– Have someone lay in one of the boxes that didn’t successfully make it to the edges and demonstrate that even if you don’t cover 1m2 per 1 min, you will likely still get a positive strike.

Components of Rescue – “Work it Backwards”

Provided by: Chris Pruden

Intro:

-Break students into rescue teams, ideally 2-3 folks per team.

-Discuss how rescue scenarios are not representative of real-world scenarios: We’re not navigating a crown, bed surface that may be full of rocks, dirt, trees, rocks, it is often hard to bury transceivers far enough away to thoroughly practice course search….

-Another key component of rescue to remember is that beacons find other beacons or really bring you close to another beacon, the probe is what actually finds the victim and shoveling is what allows this person to begin breathing again, which is the ULTIMATE goal of rescue.

-As such, we will break each step of rescue down and practice each component starting with the most valuable tool – shoveling.

Shoveling

Place a probe 1-1.5 meters deep and instruct your team to work together to get to the tip of the probe as fast as they can!

-Can set this up as shovel races for each team

-Makes sure folks are communicating and rotating

-If time allows, have teams debrief what worked well for them and what could help them be more efficient. Bury another probe and see if they can reduce their time.

Probing

Next describe components of effective probing:

● Perpendicular to the slope

● Spiral or box configuration aprox 20cm apart or about a boot-length

● Remember to move your feet as you probe to maintain perpendicular angle as your spiral or box increases in size

● Hold probe with both hands and use it to feel what you’re hitting – remember not to give so much force that you break your probe or harm the victim.

● How to tell if it’s a positive strive? Will have more of a soft, bounce or squish feel to it, probe may not sink as deeply into debris.

● LEAVE PROBE IN! Once you get a positive strike

-Demonstrate:

Slow, methodical probing in spiral or box shape with two hands and moving your feet.

Have each student do this, walk around and give feedback on movements or technique.

Fine Search

-Bury a beacon

-Demonstrate and talk through key pieces of fine search:

● Keep beacon in same orientation on XYZ axis (right, left, up, down) Only change one variable at a time.

● Slow is smooth, smooth is fast – allow for the processor to keep up with your movements!

● Make numbers go down as you work your X,Y boxes.

○ Make sure you are thoroughly checking all up, down, right, left areas before

moving on!

● Can use ski poles to mark your high readings to keep you on track

● Mark your lowest reading to start probing

Have students practice fine search in their teams – give each other feedback

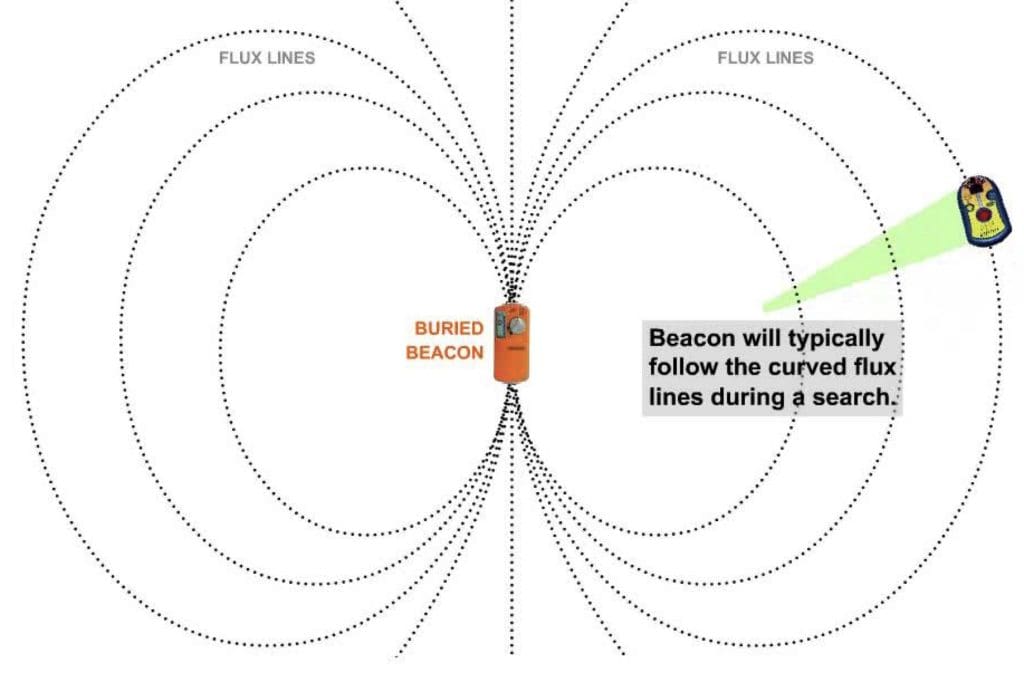

Following Signal

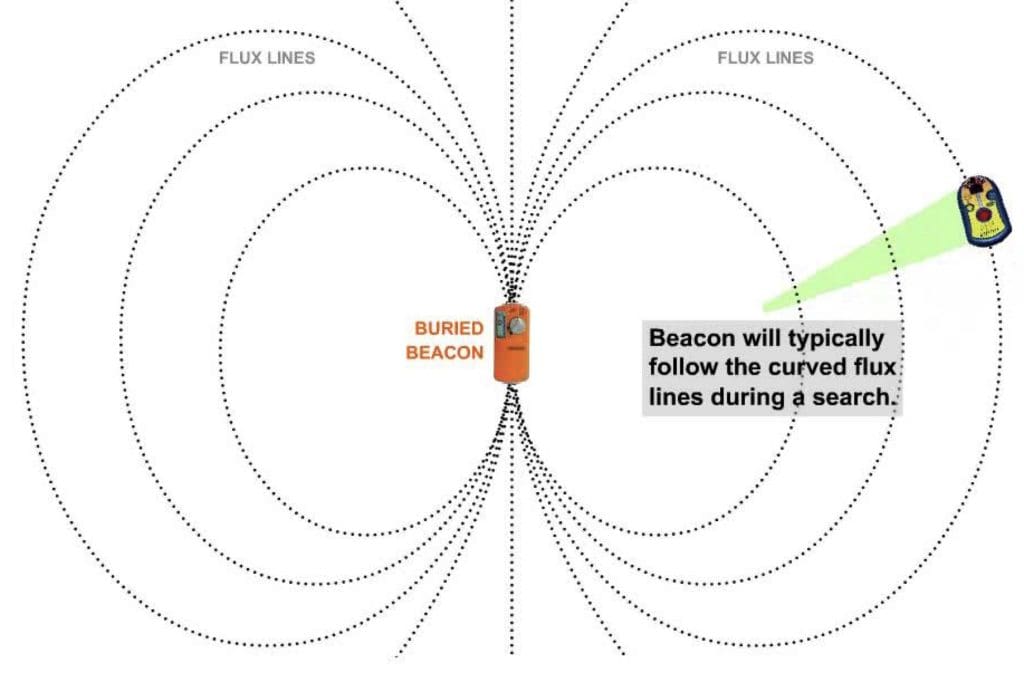

-Refresh on flux lines, beacon will likely bring you in on an arc